I confess. I read research. When looking for guidance, for a challenge, for opportunities to make better sense of education data, I look toward those in the social sciences who do this best. My work requires it. My curiosity begs for it.

The thorny questions posed by dramatic differences in the rates at which kids learn are the ones I find most tempting. Maybe I’m just related to Br’er Rabbit, eager to be thrown in that briar patch. But I am honestly motivated to plunge into the research literature by my dismay at the low level of public conversations about achievement gaps. I’m troubled by the halting efforts of education policy leaders to measure gaps sensibly. I’m astonished at the illogic applied to gap measures in Local Control Accountability Plans. And I’m disappointed that the social justice advocates are not yet making practical use of the brilliant and exciting work being done by the two researchers below: David Figlio and Sean Reardon.

David Figlio, Dean of Northwestern University’s School of Education and Social Policy

DAVID FIGLIO is an economist at Northwestern University where he is a professor of Education and Social Policy and Economics. Last September, he was appointed dean at The School of Education and Social Policy. Since that doesn’t keep him sufficiently busy, he is also a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research and at the CALDER Center. Here is where you can find his bio on the Northwestern website. Below you’ll find the articles or research papers I find most relevant to California’s inequality challenges. (Note that he has many co-authors and research assistants whose names I’ve omitted from the citations below.)

“Some Schools Much Better Than Others at Closing Achievement Gaps Between Their Advantaged and Disadvantaged Students,” Education Next, July 24, 2017. Their findings reveal that gaps in elementary school students’ test results are often greater among schools within districts, than among districts. The data that Figlio’s team used – Florida’s student longitudinal data linked to birth records – enabled them to see things that we cannot see in California because of our officials’ excessive sensitivity to student privacy legislation. Their methods are as interesting as their findings.

“Heavier Babies Do Better in School,” New York Times, October 10, 2014. This is a readable interpretation of a study David Figlio co-authored that looked at the degree to which birth weights of children were predictive of their test scores through elementary and middle school. While the effects are smaller than those of social class, the effects hold true across all ethnicities and household income categories.

“School Quality and the Gender Gap in Educational Achievement,” American Economic Review, May 2016. Figlio and his co-authors look at the degree to which school quality causes gender gaps in educational outcomes. Looking at middle school test scores, absences and suspensions, his team discovered that boys benefit more than girls from attending higher quality schools. In light of California’s pattern of girls scoring higher than boys on the English/language arts CAASPP test, this research deserves a look, to be sure.

Sean Reardon, Stanford’s Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education

SEAN REARDON is a sociologist at Stanford University whose unusual title — Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education – should lead you to expect great things. You won’t be disappointed if you do. His research focuses on the causes and consequences of social and educational inequality. Like David Figlio, he is aiming to influence policy and practices, which makes him a practical and ambitious scholar. Here is his bio on the website of Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. Together with many colleagues, Sean Reardon has built a remarkable new base of 300 million individual student test records across almost all U.S. districts, enriched with other data, and shared it with the research community at large. His energy and intellect have had a multiplier effect, stimulating others to do great work. Here is a short list of the many research works on inequality in schools that he has co-authored that you are sure to find relevant. (Again, I have omitted mentioning co-authors for the sake of brevity.)

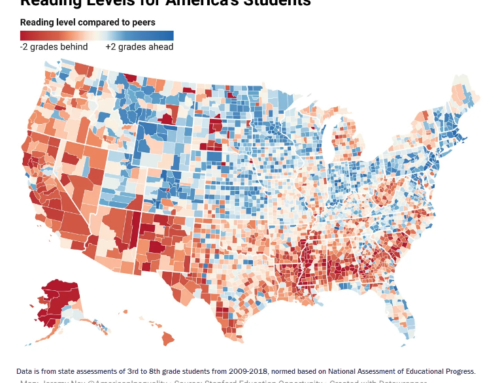

“How Effective Is Your School District? A New Measure Shows Where Students Learn the Most,” New York Times, December 5, 2017. This is an accessible newspaper summary of the stunning and original study that looked at the factors that explained the variation of gaps in test scores from 2009 through 2013, across every U.S. school district. This study concludes that between-district variation is greatest where economic and black-white segregation is highest. They used over 200 million individual student records to assemble the evidence for the study. A related study released at about the same time, with another co-author, discovered that students in grades 3 to 8 in Chicago public schools gained six years of progress in five years’ time. This put them at the top of the list of the 100 largest districts in the U.S. in the rate at which students progressed.

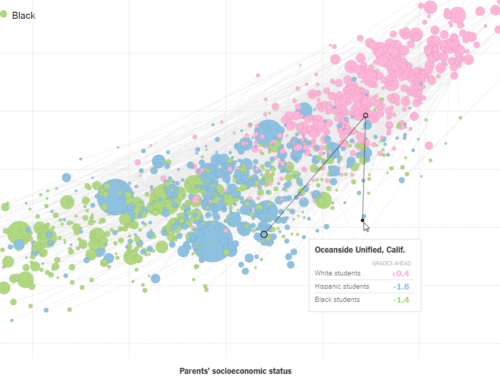

“The Geography of Racial/Ethnic Test Score Gaps,” Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis, April 2016 (first publication). This study looked at several thousand districts in several hundred metropolitan areas, and found huge variations (12 to 1) in the size of the gaps of students’ test scores, based on ethnicity and household income. This excellent New York Times article, “Money, Race and Success,” explains the study, and offers an interactive way for you to see where your district stands, if it’s among the nation’s 2,000 largest districts. Gaps in test scores (converted to years of schooling) are expressed along a spectrum of household income in a dynamic scatterplot and a ranking table.

“The Good News About Educational Inequality,” New York Times, August 26, 2016. This article, which was co-authored by Sean Reardon, offers an interesting insight into a happy discovery. Too quote from their op-ed: “The enormous gap in academic performance between high- and low-income children has begun to narrow. Children entering kindergarten today are more equally prepared than they were in the late 1990s.”

“No Rich Child Left Behind,” New York Times, April 27, 2013. In this op-ed essay, Sean Reardon looked at the education consequences of increasing gaps in household income. What he saw is that gaps separating lower income and higher income students’ test scores have increased more in thirty years than the gap in black and white students’ scores. He asserts that family income is now a better predictor of children’s success in school than race. SAT scores of students are 1.8 times as large based on differences in household income than on ethnic identity. The research paper on which this essay is based is “The Widening Income Achievement Gap.”

A handful of other engaged scholars also deserve attention, for the quality and relevance of their work to California’s gap challenges. Among them are: Susan Dynarski, Caroline Hoxby, and Andrew Ho.